“We are a country of all extremes, ends and opposites; the most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world … In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name or number.”

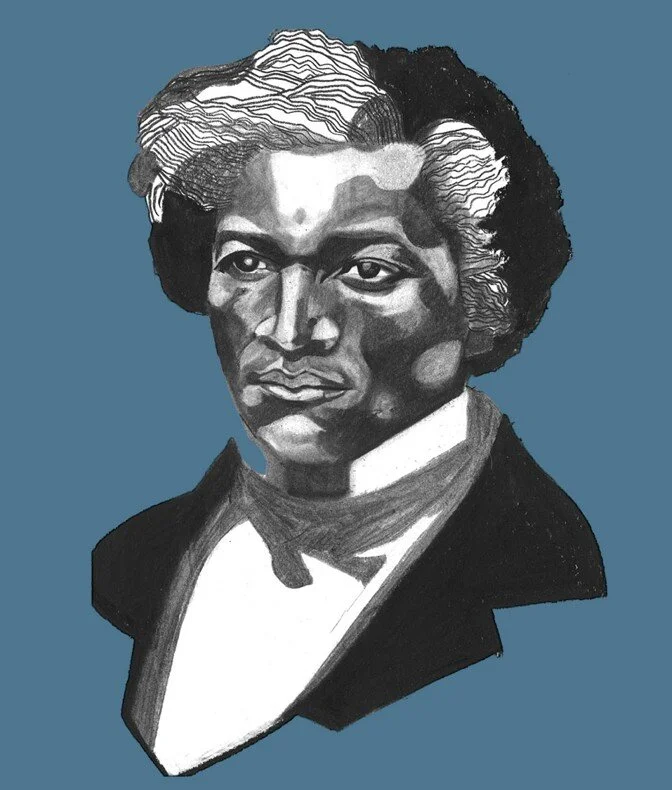

— Frederick Douglass, 1869

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, he dreamed of a pluralist utopia.

By David W. Blight, December 2019 Issue

In the late 1860s, Frederick Douglass, the fugitive slave turned prose poet of American democracy, toured the country spreading his most sanguine vision of a pluralist future of human equality in the recently re-United States. It is a vision worth revisiting at a time when the country seems once again to be a house divided over ethnicity and race, and over how to interpret our foundational creeds.

The Thirteenth Amendment (ending slavery) had been ratified, Congress had approved the Fourteenth Amendment (introducing birthright citizenship and the equal-protection clause), and Douglass was anticipating the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment (granting black men the right to vote) when he began delivering a speech titled “Our Composite Nationality” in 1869. He kept it in his oratorical repertoire at least through 1870. What the war-weary nation needed, he felt, was a powerful tribute to a cosmopolitan America—not just a repudiation of a divided and oppressive past but a commitment to a future union forged in emancipation and the Civil War. This nation would hold true to universal values and to the recognition that “a smile or a tear has no nationality. Joy and sorrow speak alike in all nations, and they above all the confusion of tongues proclaim the brotherhood of man.”

(From December 1866: Frederick Douglass’s ‘Reconstruction’)

Douglass, like many other former abolitionists, watched with high hopes as Radical Reconstruction gained traction in Washington, D.C., placing the ex–Confederate states under military rule and establishing civil and political rights for the formerly enslaved. The United States, he believed, had launched a new founding in the aftermath of the Civil War, and had begun to shape a new Constitution rooted in the three great amendments spawned by the war’s results. Practically overnight, Douglass even became a proponent of U.S. expansion to the Caribbean and elsewhere: Americans could now invent a nation whose egalitarian values were worth exporting to societies that were still either officially pro-slavery or riddled with inequality.

The aspiration that a postwar United States might slough off its own past identity as a pro-slavery nation and become the dream of millions who had been enslaved, as well as many of those who had freed them, was hardly a modest one. Underlying it was a hope that history itself had fundamentally shifted, aligning with a multiethnic, multiracial, multireligious country born of the war’s massive blood sacrifice. Somehow the tremendous resistance of the white South and former Confederates, which Douglass himself predicted would take ever more virulent forms, would be blunted. A vision of “composite” nationhood would prevail, separating Church and state, giving allegiance to a single new Constitution, federalizing the Bill of Rights, and spreading liberty more broadly than any civilization had ever attempted.

Was this a utopian vision, or was it grounded in a fledgling reality? That question, a version of which has never gone away, takes on an added dimension in the case of Douglass. One might well wonder how a man who, before and during the war, had delivered some of the most embittered attacks on American racism and hypocrisy ever heard could dare nurse the optimism evident from the very start of the speech. How could Douglass now believe that his reinvented country was, as he declared, “the most fortunate of nations” and “at the beginning of our ascent”?

(From December 2018: Randall Kennedy on the confounding truth about Frederick Douglass)

Few Americans denounced the tyranny and tragedy at the heart of America’s institutions more fiercely than Douglass did in the first quarter century of his public life. In 1845, seven years after his escape to freedom, Douglass’s first autobiography was published to great acclaim, and he set off on an extraordinary 19-month trip to the British Isles, where he experienced a degree of equality unimaginable in America. Upon his return, in 1847, he let his profound ambivalence about the concepts of home and country be known. “I have no love for America, as such,” he announced in a speech he delivered that year. “I have no patriotism. I have no country.” Douglass let his righteous anger flow in metaphors of degradation, chains, and blood. “The institutions of this country do not know me, do not recognize me as a man,” he declared, “except as a piece of property.” All that attached him to his native land were his family and his deeply felt ties to the “three millions of my fellow-creatures, groaning beneath the iron rod … with … stripes upon their backs.” Such a country, Douglass said, he could not love. “I desire to see its overthrow as speedily as possible, and its Constitution shivered in a thousand fragments.”

Six years later, as the crisis over slavery’s future began to tear apart the nation’s political system, Douglass intensified his attacks on American hypocrisy and wanted to know just who could be an American. “The Hungarian, the Italian, the Irishman, the Jew and the Gentile,” he said about the huge waves of European immigration, “all find in this goodly land a home.” But “my white fellow-countrymen … have no other use for us [blacks] whatever, than to coin dollars out of our blood.” Demanding his birthright as an American, he felt like only the “veriest stranger and sojourner.”

The fact that emancipation, extracted through blood and agony, could so quickly transform Douglass into the author of a hopeful new vision of his country is stunning, a testament to the revolutionary sense of history embraced by this former slave and abolitionist. Yet he had always believed that America had a “mission”—that the United States was a set of ideas despite its “tangled network of contradictions.” Now the time had come to reconceive the mission. Douglass’s immediate post–Civil War definition of a nation came quite close to the Irish political scientist Benedict Anderson’s modern conception of an “imagined community.” In his “Composite Nationality” speech, Douglass explained that nationhood “implies a willing surrender and subjection of individual aims and ends, often narrow and selfish, to the broader and better ones that arise out of society as a whole. It is both a sign and a result of civilization.” And a nation requires a story that draws its constituent parts into a whole. The postwar United States served as a beacon—“the perfect national illustration of the unity and dignity of the human family.”

Americans needed a new articulation of how their country was an idea, Douglass recognized, and he gave it to them. Imagine the audacity, in the late 1860s, to affirm the following for the reinvented United States:

A Government founded upon justice, and recognizing the equal rights of all men; claiming no higher authority for its existence, or sanction for its laws, than nature, reason and the regularly ascertained will of the people; steadily refusing to put its sword and purse in the service of any religious creed or family.

Few better expressions exist of America’s founding principles of popular sovereignty, natural rights, and the separation of Church and state. From his enslaved youth onward, Douglass had loved the principles and hated their flouting in practice. And he had always believed in an Old Testament version of divine vengeance and justice, sure that the country would face a rending and a renewal. Proudly, he now declared such a nation a “standing offense” to “narrow and bigoted people.”

In the middle section of his speech, Douglass delivered a striking argument on behalf of Chinese immigration to America, then emerging as an important political issue. In the Burlingame Treaty, negotiated between the U.S. and the empire of China in 1868, the American government acknowledged the “inalienable right” of migration and accepted Chinese immigrants, but it denied them any right to be naturalized as citizens. Douglass predicted a great influx of Chinese fleeing overcrowding and hunger in their native country, and finding work in the mines and expanding railroads in the West. They would surely face violence and prejudice, Douglass warned. In language that seems timely today, he projected himself into the anti-immigrant mind. “Are not the white people the owners of this continent?” he asked. “Is there not such a thing as being more generous than wise? In the effort to promote civilization may we not corrupt and destroy what we have?”

But this rhetorical gesture of empathy for the racists gave way to a full-blown attack. He urged Americans not to fear the alien character of Asian languages or cultures. The Chinese, like all other immigrants, would assimilate to American laws and folkways. They “will cross the mountains, cross the plains, descend our rivers, penetrate to the heart of the country and fix their home with us forever.” The Chinese, the “new element in our national composition,” would bring talent, skill, and laboring ethics honed over millennia. Douglass invoked the morality of the natural-rights tradition. “There are such things in the world as human rights. They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are eternal, universal and indestructible.” Migratory rights, he asserted, are “human rights,” and he reminded Americans that “only one-fifth of the population of the globe is white and the other four-fifths are colored.”

Just as important, he placed the issue in the context of America’s mission. The United States ought to be a home for people “gathered here from all quarters of the globe.” All come as “strangers,” bringing distinct cultures with them, but American creeds can offer a common ground. Though conflict may ensue, a nation of “strength and elasticity” would emerge through contact and learning. What might sound like a manifesto for multicultural education in the 1990s or a diversity mission statement at any university today actually has a long history.

Douglass made sure to embed his bold vision in first principles. To the argument that it is “natural” for people to collide over their cultural differences and to see one another only through mutual “reproachful epithets,” he countered with the notion that “nature has many sides,” and is not static. “It is natural to walk,” Douglass wrote, “but shall men therefore refuse to ride? It is natural to ride on horseback, shall men therefore refuse steam and rail? Civilization is itself a constant war upon some forces in nature, shall we therefore abandon civilization and go back to savage life?” Douglass called on his fellow citizens to recognize that “man is man the world over … The sentiments we exhibit, whether love or hate, confidence or fear, respect or contempt, will always imply a like humanity.” But he did not merely ask Americans to all get along. He asked his fellow countrymen to make real freedom out of slavery, out of their sordid history—to see that they had been offered a new beginning for their national project, and to have the courage to execute it.

Swept up in hope, Douglass did not anticipate the rising tide of nativism that lay ahead in the Gilded Age. The U.S. passed a first Chinese-exclusion law, directed at women who were deemed “immoral” or destined for forced labor, in 1875. By 1882, Sinophobia and violence against the Chinese led to the federal Chinese Exclusion Act, banning virtually any immigration by the group—the first such restrictive order against all members of a particular ethnicity in American history. Those who remained in the country lived constrained and dangerous lives; in the late 1880s, Chinese miners were gruesomely massacred in mines across the West. The Chinese also faced the hostility of white workers who now fashioned the ideology of “free labor” into a doctrine that sought to eliminate any foreign competition for jobs, especially in economic hard times. For Douglass, these bleak realities were just the outcomes he had warned against as Reconstruction gathered momentum.

Immigrants from Europe continued to stream into the United States, even as a resurgent white South gained control of its society in the latter days of Reconstruction. As nativism, racism, and nationalism converged in the closing decades of the 19th century, the idea of America as a cosmopolitan nation of immigrants fought for survival. Eugenics acquired intellectual legitimacy; and violence, and eventually Jim Crow laws, consolidated a system of white supremacy.

(Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia to rival the great universities in the North and transform a slave-owning generation. As the university celebrates its 200th anniversary, Annette Gordon-Reed reviews Alan Taylor’s new book about how Jefferson’s plan was launched.)

By the 1890s Douglass, aging and in ill health but still out on the lecture circuit, felt hard-pressed to sustain hope for the transformations at the heart of the “Composite Nationality” speech. He never renounced his faith in natural rights or in the power of the vote. But in the last great speech of his life, “Lessons of the Hour”—an excoriating analysis of the “excuses” and “lie” at the root of lynching—Douglass betrayed a faith “shaken” and nearly gone. Disenfranchisement and murderous violence left him observing a nation mired in lawless horror. Lynchings were “lauded and applauded by honorable men … guardians of Southern women” who enabled other men to behave “as buzzards, vultures, and hyenas.” A country once endowed with “nobility” was crushed by mob rule. His dream in tatters, Douglass begged his audiences to remember that the Civil War and Reconstruction had “announced the advent of a nation, based upon human brotherhood and the self-evident truths of liberty and equality. Its mission was the redemption of the world from the bondage of ages.”

Many civil wars leave legacies of continuing conflict, renewed bloodshed, unstable political systems. Ours did just that, even as it forged a new history and a new Constitution. In 2019, our composite nationality needs yet another rebirth. We could do no better than to immerse ourselves in Douglass’s vision from 1869. Nearly 20 years earlier, he had embraced the exercise of human rights as “the deepest and strongest of all the powers of the human soul,” proclaiming that “no argument, no researches into mouldy records, no learned disquisitions, are necessary to establish it.” But the self-evidence of natural rights, as Douglass the orator knew, does not guarantee their protection and practice. “To assert it, is to call forth a sympathetic response from every human heart, and to send a thrill of joy and gladness round the world.” And to keep asserting those rights, he reminds us, will never cease to be necessary.

Practicing them is crucial too. In an 1871 editorial he took a position worth heeding today. The failure to exercise one’s right to vote, he wrote, “is as great a crime as an open violation of the law itself.” Only a demonstration of rebirth in our composite nation and of vibrancy in our democracy will again send thrills of joy and emulation around the world about America. Such a rebirth ought not to be the object of our waiting but of our making, as it was for the Americans, black and white, who died to end slavery and make the second republic.

This article appears in the December 2019 print edition with the headline “The Possibility of America.”

Article in The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/12/frederick-douglass-david-blight-america/600802/